|

|

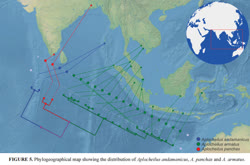

"In his work on the fishes of the Andaman Islands, Francis Day (1870) collected large-sized specimens of Aplocheilus from

the south Andamans. Despite differences in the size and dorsal-fin ray counts, Day refrained from recognising the Andaman

Aplocheilus as a distinct species and considered it as Aplocheilus panchax, a species distributed in the Ganges delta

and across the eastern coast of mainland India. However, Day mentioned the differences in fin-ray counts between these

two populations. Subsequently Köhler (1906) described the Andaman population as Haplochilus andamanicus (now in

Aplocheilus), referring to the diagnostic characters initially discovered by Day. This species failed to receive recognition

from taxonomists, because of the uncertainty regarding the validity of the species and its questionable synonymy with A.

panchax. In this study, based on morphological and molecular evidence, we demonstrate that A. andamanicus is indeed a

distinct and valid species, which can easily be diagnosed from the widespread A. panchax." - Katwate et al. 2018

- DOI: 10.11646/zootaxa.4382.1.6

"In this study, based on morphological and molecular evidence, we demonstrate that A. andamanicus is indeed a

distinct and valid species, which can easily be diagnosed from the widespread A. panchax."

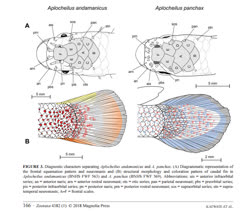

Aplocheilus andamanicus differs

from topotypic A. panchax by the combination of the following characters: the most discussed (Day, 1878; Köhler

1906; Herre, 1939) being body size difference, A. andamanicus grows much larger in size (it is probably the largest

Aplocheilus in South and South-East Asia), to at least 74.8 mm SL (vs. smaller in size); 9–10 dorsal-fin rays (vs.

6–8); 15 principal and 18–19 procurrent caudal-fin rays (vs. 12–13 principal and 12 procurrent caudal-fin rays);

dorsal fin with posterior margin widely separated from caudal-fin base or hypural plate (vs. extending beyond

vertical through caudal base or hypural plate); pectoral fin extending beyond vertical through anterior one-third of

pelvic fin (vs. pectoral fin extending to half the length of pelvic fin); pelvic fin nearly reaching vent when

adpressed but well separated from anterior base of anal fin (vs. pelvic fin extends beyond vent reaching anterior

base of anal fin); caudal-fin margin rounded (vs. more oval in) (Fig. 3); lateral line system incomplete extending up

to the vertical from posterior margin of dorsal fin base (vs. lateral line system complete, reaching caudal-fin base);

total vertebrae 33–34 (vs. 28–30); pre-anal vertebrae 13–14 (vs. 11–12); caudal vertebrae 18–19 (vs. 14–16);

median scale “A” of frontal squamation pattern smaller than scale “B” (vs. median scale “A” significantly larger

than scale “B”) (Fig. 3); single anterior rostral and posterior rostral neuromasts (vs. 2 anterior rostral and 3

posterior rostral neuromasts). Day (1878) reported a total of up to 11 dorsal-fin rays in his Andaman collection, a

character that was subsequently used by Köhler (1906) to diagnose A. andamanicus. Radiographs of Day’s

collection (syntypes, BMNH 1889.2.1.2107-2110) and cleared and stained topotypes (BNHS FWF 384 & 385) of

A. andamanicus showed, however, only 9–10 dorsal-fin rays. In any case, the dorsal-fin ray count is still valid and

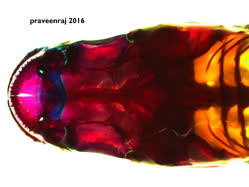

is the most significant diagnostic character that distinguishes A. andamanicus from A. panchax (9–10 vs. 7–8).Furthermore, A. andamanicus can easily be distinguished from A. panchax based on its unique coloration

pattern including, dorsal fin extremity deep yellow or saffron (vs. blue in A. panchax); distal half of anal fin hyaline

in female or studded with three longitudinal rows of vertically elongated red dots (vs. distal half of anal fin deep

iridescent blue); pelvic fin yellow (vs. hyaline in A. panchax); and caudal fin periphery hyaline or subtle red (vs.

deep iridescent blue in A. panchax). Both species are also genetically distinct, with a cox1 distance of 9.6–10.8%

(Table 2) - Katwate et al. 2018

|